As data privacy protection has become a priority for individuals, governments at all levels have enacted a variety of privacy rights laws to control how organizations collect, store and process personal information, such as names, addresses, healthcare data, financial records, and credit information.

Learn more about data privacy laws in the US, as well as what changes and other developments to expect for existing laws governing personal data.

Data privacy laws in the U.S.

How is data privacy enforced in the US?

The need to address modern privacy issues and protect data privacy rights is a global trend. One defining moment came in May 2018, when the EU implemented the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), an extensive piece of legislation that applies not only to EU member states but any organization that collects or processes the data of European residents.

Simply put, the United States has no equivalent to the EU’s GDPR. Indeed, as of 2021, the US is one of the only democracies and the sole member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development that doesn’t have a federal data protection agency, though Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and others have proposed the creation of one. With no comprehensive data protection law at the federal level, the US continues to regulate data privacy through a mix of laws passed at the state and federal levels.

Companies need to be aware of all relevant legislation before they start collecting or processing any data that could be deemed “personal information.” Failure to follow applicable data privacy acts can lead to lawsuits and fines.

Federal privacy laws in the US and their enforcement

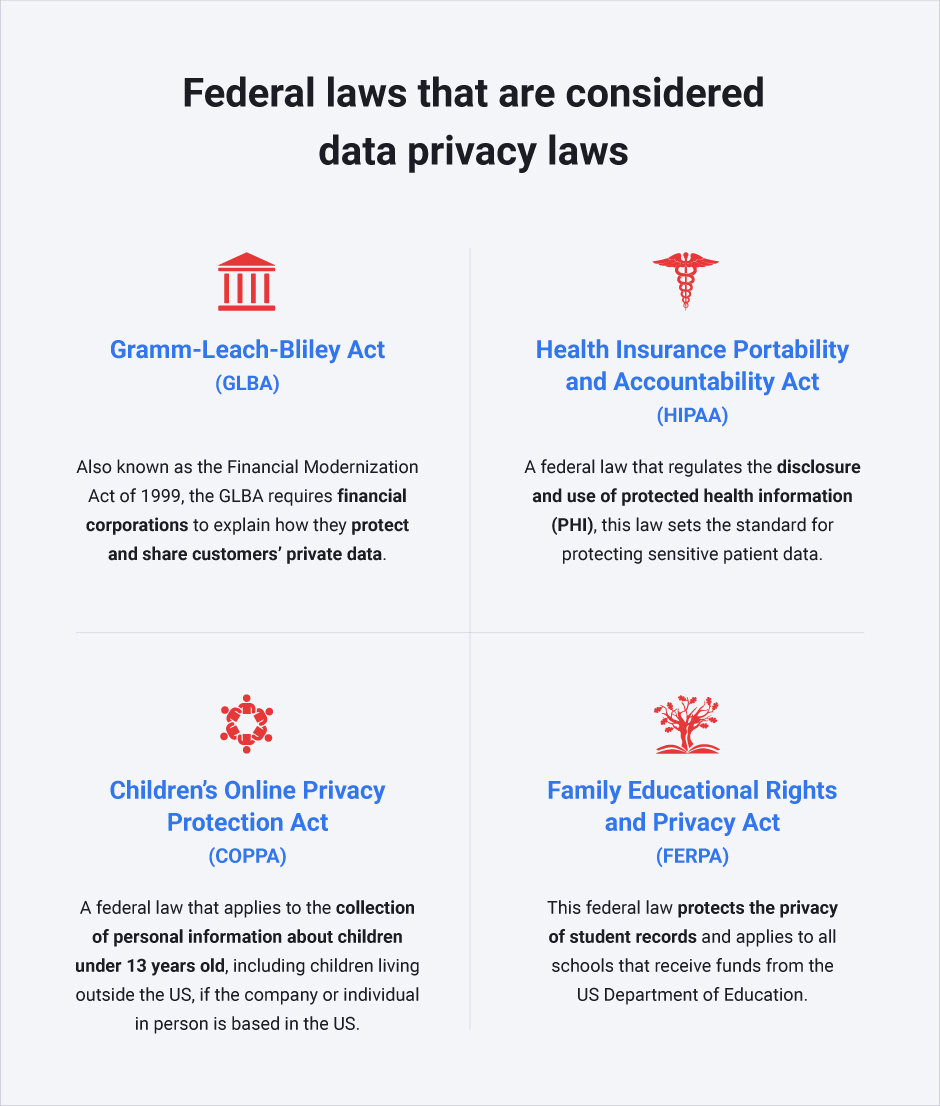

Federal laws that are considered data privacy laws include:

- Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA): Also known as the Financial Modernization Act of 1999, the GLBA requires financial corporations to explain how they protect and share customers’ sensitive

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA): This federal law regulates the disclosure and use of protected health information (PHI).

- Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA): This law restricts the collection of personal information about children under 13 years old.

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA): This federal law protects the privacy of student records and applies to all schools that receive funds from the US Department of Education.

- Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA): Governs the collection and use of consumer information

At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has broad jurisdiction over commercial entities to prevent “deceptive trade practices,” which may include data privacy issues. The FTC has the authority to enforce privacy laws, issue regulations, and take actions to protect consumers. In particular, the FTC can act against companies that:

- Fail to create, implement and maintain reasonable data security breach measures

- Violate consumer data privacy rights by collecting, processing, or sharing consumer information without their consent

- Publish and establish inaccurate or confusing privacy and security policies to consumers on websites and apps

- Collect, process, transfer, or share personal information in a way that’s not disclosed in the privacy policy

State-level data privacy laws in the US

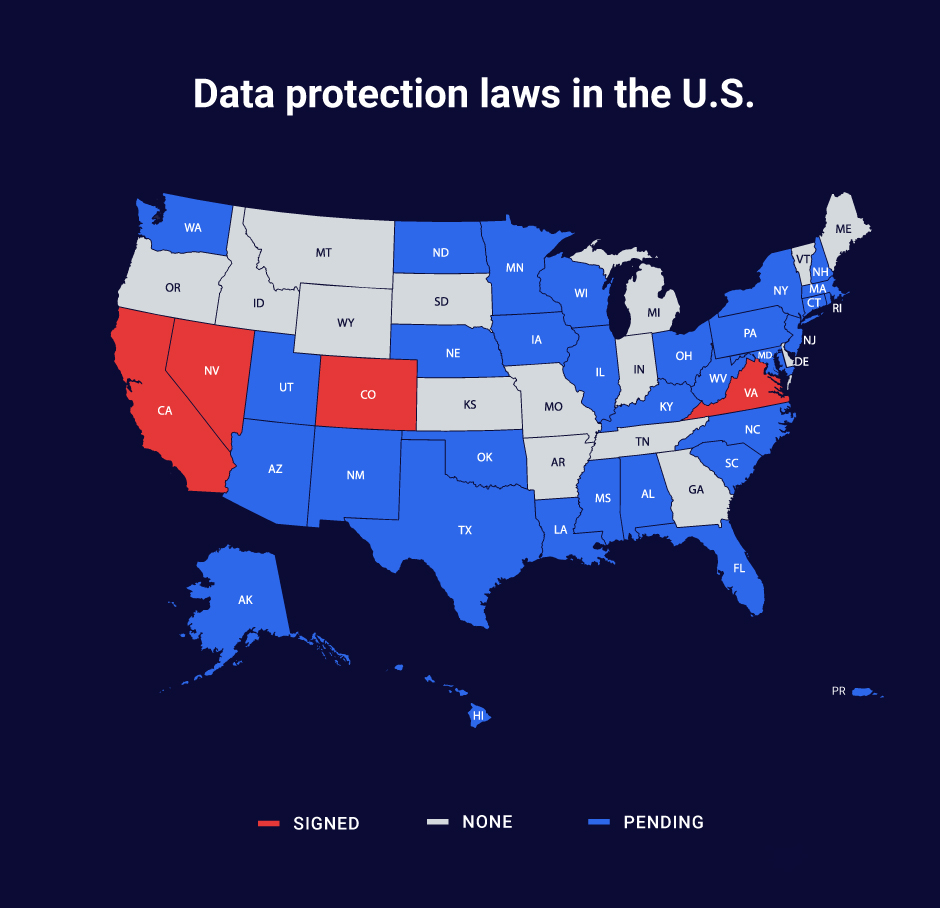

Many US states also have their own data privacy and security laws. State attorney general offices are responsible for overseeing these laws.

State-level regulations often have overlapping or incompatible provisions. For example, all 50 US states have adopted data breach notification laws, but there are differences in the definition of personal data and even in what constitutes a data breach. Similarly, at least 35 states (and Puerto Rico) have enacted some form of data disposal regulations, with many of these laws addressing digital data specifically.

Here are the key data privacy laws by state that have been enacted:

California Consumer Privacy Act

Effective date: January 1, 2020

Provisions: This California data privacy law started as a ballot initiative in response to growing public concern about the amount of private data that digital and technology businesses in Silicon Valley have been quietly collecting and selling for decades. The California law incorporates the core principles of the data protection and data privacy requirements in the European Union’s GDPR.

The CCPA governs the collection, sale, and disclosure of the personal information of California residents. It applies to the activity of businesses, service providers that serve businesses, and third parties (which can be individuals or organizations). One of the key terms of the law is that businesses must respond promptly to inquiries of California consumers regarding what personal data is being collected about them and whether it is being sold or disclosed. The law allows for no discrimination against consumers who exercise their rights; consumers must be given the same quality of service even if they object to a particular activity, such as the sale of their data. Service providers may use consumer data only at the direction of the business they serve and must delete a consumer’s personal information from their records upon request.

Scope: The CCPA applies to every for-profit business operating in California that satisfies certain conditions, such as a revenue threshold. It has an extraterritorial effect, as it covers non-CA businesses that operate in California.

Other key facts:

- Certain sensitive data is exempt from CCPA requirements, including protected health information (PHI) already covered by the Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act (HIPAA), medical information already covered by the California Confidentiality of Medical Information Act, and some information covered by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA).

- The law currently requires businesses to extend the rights provided by the CCPA to their employees. However, there is a pending bill that would amend that law to exclude employees from the definition of “consumer.”

- When a business receives an inquiry about the information collected and stored about an individual, it must verify that the person making the request is actually who they claim to be before responding.

Penalties for violations: The law gives companies 30 days to “cure” violations. Failure to address a violation leads to a civil penalty of up to US$7,500 for each intentional violation and US$2,500 for each unintentional violation.

California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)

Official name: Proposition 24

Effective date: January 1, 2023, but won’t be enforced until July 1, 2023

Provisions: This California law gives new rights to consumers, such as the right to:

- Correct inaccurate information.

- Have personal information collected subject to purpose limitations and data minimization.

- Receive notice from businesses planning to use sensitive personal information and ask them to stop. This includes biometric information, genetic data, and any information concerning an individual’s health, sexual orientation, or sex life.

Scope: This law has a wider scope than the CCPA since it offers the following expanded rights to consumers:

- The right to sue businesses when they expose passwords and usernames: The CPRA expands the CCPA’s definition of “personal information” to include usernames and passwords.

- The right to opt out of sharing information with third parties: Under the CCPA, this was a debated point because “sell” did not explicitly include sharing. With CPRA, consumers can now opt out of the sale and sharing of personal information to third parties.

- The right to access more information: Consumers can request access to any personal information collected by a business, not just information collected in the preceding 12-month period.

Other key facts: This law also creates a new privacy agency, the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA), which will be responsible for enforcement.

Penalties for violations: Fines can be anywhere from $2,500 to $7,500, depending on whether you’re a business or an individual. There are also automatic fines of $7,500 for violations of the data of minors (anyone under the age of 16).

Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

Official name: SB 21-190

Effective date: July 1, 2023

Provisions: The CPA applies to “controllers” that operate in Colorado or deliver products or services targeted to residents of Colorado that:

- Control or process the personal data of 100,000 or more consumers in one year

- Obtain revenue or get discounts on the price of services or goods from selling, processing, or controlling the personal data of 25,000 or more consumers

Starting on July 1, 2024, controllers that meet the above requirements must honor opt-outs for targeted sales and advertising. CPA also gives Colorado residents the right to access, correct, and delete their personal data, in addition to the right to data portability. Controllers will have 45 days to respond to requests.

Scope: Unlike the California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018, the CPA does not have a monetary threshold for applicability. This means every business needs to consider this law. However, it does not apply to the following institutions:

- Financial institutions subject to the GLBA

- Various types of healthcare-related data

- Data governed by FERPA

Unlike the California laws, CPA does not exclude nonprofits.

Other key facts: CPA makes it necessary for controllers to enter into data processing agreements (DPAs) with processors. Controllers will also need to conduct and log data protection assessments.

Penalties for violations: There is no private right of action, so the Attorney General of Colorado and district attorneys will enforce the CPA. They can seek monetary damages or injunctive relief. Before taking action, however, the Attorney General and the district attorneys must issue a notice of violation and allow companies or individuals 60 days to cure the alleged violation. After January 2025, this “right to cure” will be replaced by the controller’s right to request guidance from the Attorney General’s office.

Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (CDPA)

Official name: SB-1392

Effective date: January 1, 2023

Provisions: The CDPA provides consumers with six rights:

- Right to correct

- Right to access

- Right to data portability

- Right to delete

- Right to opt-out

- Right to appeal

Scope: This law applies to entities that conduct business in Virginia or create services or products that are targeted to Virginia residents that:

- Control or process the personal data of more than 100,000 consumers during a year

- Control or process the personal data of more than 25,000 consumers and derive at least half of their gross revenue from the sale of personal data

Like Colorado’s CPA, Virginia’s CPDA does not have a revenue threshold. This means that businesses of all sizes need to pay attention to this law.

The definition of “consumer” does not include a person acting in an employment or commercial context. This makes it different from the CPRA, which includes employee data. Accordingly, businesses will not have to consider employee data when deciding whether the CPDA applies to them.

Other key facts: Like the EU’s GDPR and California’s CCPA, the CDPA has a provision limiting the collection of data to that which is “adequate, relevant and reasonably necessary in relation to the purposes for which the data is processed.”

Penalties for violations: Like Colorado’s CPA, Virginia’s CDPA does not have a private right of action. Enforcement is the Attorney General’s responsibility. The controller has 30 days to cure the violation after the Attorney General notifies the controller that action will be taken. If the controller fails to cure the violation within this period, the Attorney General may fine them up to $7,500 per violation.

Nevada Internet Privacy Bill (SB260)

Official name: BDR-52-253

Effective date: October 1, 2021

Provisions: This law will provide Nevada residents with a broader right to opt out of the sale of their personal information. It also creates new requirements for “data brokers,” which are defined as entities whose primary means of business is selling information about consumers from operators or other data brokers. Data brokers must establish a designated address through which consumers may request the data broker to stop selling their information. The data broker will have to respond within 60 days of receipt.

Scope: The law expands the scope of the opt-out right, but the scope of “covered information” is narrower than “personal information” defined by similar laws.

“Covered information” is limited to:

- First and last names

- Home/physical addresses

- Email address

- Telephone numbers

- Social security numbers

- Identifiers that allow the person to be contacted in person or online

Other key facts: The bill amends Nevada’s online privacy notice statutes, such as NRS 603A.300-360.

Penalties for violations: Nevada’s Attorney General is tasked with enforcing this law. The court will issue a temporary or permanent injunction or a civil penalty of up to $5,000 per violation.

Massachusetts Data Privacy Law

Official name: Standards for The Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth (201 CMR 17.00)

Effective date: March 1, 2010

Provisions: This law provides requirements to protect Massachusetts residents against identity theft and fraud.

Scope: Any organization that licenses, stores or maintains personal data about Massachusetts residents are required to implement a comprehensive information security program.

Other key facts:

- The law requires companies to have a dedicated person to run a data security program and conduct regular employee training.

- The law also requires businesses to take “reasonable steps” to verify that third-party service providers with access to personal information can protect that information.

- The law protects the security and confidentiality of both consumer and employee personal information, which includes first name, last name, Social Security number, driver’s license number, state-issued ID card number, financial account number, credit or debit card number, and any access code that enables access to a person’s financial information. However, it excludes information obtained from publicly available sources.

- Massachusetts is also working on a CCPA-like data privacy regulation. If passed, SD.341 “An Act Relative to Consumer Data Privacy,” is slated to go into effect January 1, 2023.

Penalties for violations: The Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation is responsible for enforcement. Each intentional violation of the law can incur a civil penalty of up to US$5,000, plus “reasonable costs of investigation and litigation of such violation, including reasonable attorneys’ fees.”

Minnesota Data Privacy Act

Official name: Minnesota Government Data Practices Act (MGDPA) (Minn. Stat. § 13)

Effective date: 1979

Provisions: This Minnesota statute protects individuals’ right to access government data, and controls the collection, storage, use, and dissemination of private data. It establishes a classification system to differentiate different types of information, such as education data and law enforcement data. In addition, data about individuals is tagged as public or nonpublic, while data not on individuals is tagged as nonpublic or protected nonpublic

Scope: The law applies to any Minnesota government entity.

Other key facts:

- The law requires that every state agency appoint a “responsible authority” who will establish procedures to ensure that data requests are “received and complied with an appropriate and prompt manner.” If a government entity wants to collect an individual’s private or confidential data, the entity must give that individual a privacy notice called a “Tennessen”

- In case of a dispute between a government entity and a person regarding data practices, the person can request an advisory opinion from the Commissioner of Administration.

Penalties for violations: Penalties can include a civil action for a willful violation, or attorney’s fees if the government entity fails to follow the advisory opinion. For willful violations, the court can also impose criminal penalties on public employees, suspend them without pay or dismiss them.

Proposed US State Data Privacy Laws

All the data privacy laws above have been enacted, but there are laws being discussed. They include the following:

Ohio Personal Privacy Act (OPPA)

Official name: House Bill 376

Description: This bill is similar to legislation established in California, Virginia, and Colorado. If enacted, it will give Ohioans certain digital rights, and impose obligations on any business that collects the personal data of Ohio consumers.

Consumer Privacy Act of North Carolina (CPA)

Official name: Senate Bill 569

Description: If enacted, this law would give North Carolina consumers the following rights:

- Right of knowledge and access

- Right to correction

- Right to deletion

- Right to opt out

- Private right of action

It will apply to all businesses that target their services and products to North Carolina residents and that:

- Process or control the personal data of 100,000 or more consumers yearly

- Process or control the personal data of at least 25,000 consumers and derive over half of the gross revenue from the sale of this personal data.

Rhode Island Data Transparency and Privacy Protection Act

Official name: HB 5959

Description: This bill outlines information sharing practices and requires transparency in the way consumer data is collected, requiring certain companies to provide privacy policy disclosures. If passed, the law will help consumers identify the personal information collected, shared, or sold to third parties by online service providers and commercial websites.

Pennsylvania Consumer Data Privacy Act

Official name: House Bill 1126

Description: This act would apply to for-profit companies that meet all of the following criteria:

- Do business in Pennsylvania

- Collect, share or sell consumers’ personal information

- Determine alone or with others the purposes and means of processing consumers’ personal information

- Meet one of the following requirements:

- Derive half their annual income from the sale of consumers’ personal information

- Annually buy, share or sell (alone or with others) the personal information of 50,000 consumers, devices, or households

- Have an annual gross revenue of at least $10 million

New Jersey — Three Data Privacy Bills

Official names: A5448, A3283, and A3255

Description:

A5448 and A3255 have similar goals: They would require businesses to notify consumers of collection and disclosure of personally identifiable information and allow consumers to opt out.

A3283, the New Jersey Disclosure and Accountability Transparency Act (NJ DaTA), would set requirements for the disclosure and processing of personally identifiable information. The bill would also establish an Office of Data Protection and Responsible Use in the Division of Consumer Affairs.

Massachusetts Information Privacy Act (MIPA)

Official name: S.46

Description: This bill is a modified version of the People’s Privacy Act in the state of Washington. It would protect consumers from unauthorized collection, use, and monetization of their personal information, including location and biometric data; prohibit discrimination based on personal information, and protect workers against unwarranted electronic monitoring on the job.

Hawaii Consumer Privacy Protection Act

Official name: SB 418

Description: This proposed bill will grant consumers the right to access, delete and opt out of the sale of their personal information. Like the CCPA, it has a broad definition of “personal information.” It has the same major protections and rights as CCPA, but it doesn’t define what a “business” is so it doesn’t exclude businesses by size.

New York Consumer Privacy Act (NYPA)

Official name: Senate Bill S567

Description: This proposed New York data privacy law is very similar to the CCPA. It would empower individuals to know what data a business has collected about them and whom they have shared it with, request that the business correct or delete the data, and opt out of having their data shared with or sold to third parties. The NYPA would complement New York’s existing data breach notification law by expanding the protection of personal information.

The proposed bill sets high data privacy protection standards, such as the following:

- It imposes fiduciary duties on any legal entity that collects, sells, or licenses personal data, and defines those duties broadly. Businesses must secure consumers’ personal data against any risk that affects them. Moreover, it says that the data fiduciary responsibility supersedes “any duty owed to owners or shareholders.”

- It is stronger than other state laws in that it requires businesses to put their customers’ privacy before their own profits. This privacy legislation has a very controversial line that says that organizations should “act in the best interests of the consumer.” It does not explain, however, what companies should actually understand about the interests of New Yorkers and other customers.

- It offers a private right of action — giving consumers the right to sue companies directly over privacy violations rather than leaving enforcement to the state Attorney General.

Conclusion

US states are enacting their own data privacy and cybersecurity regulations since, unlike the EU, the US has yet to pass a comprehensive federal data privacy law. The situation will continue to get more complex as more state laws come into effect in the coming months and years. To avoid steep penalties, lawsuits, and other consequences of compliance failures, organizations should carefully review data privacy laws in the US and ensure they meet all applicable requirements.

F.A.Q.

Which U.S. laws impose requirements for securing data privacy?

In the absence of comprehensive federal legislation regulating data privacy, the U.S. is governed by sector-specific and state-specific laws that control the sharing of particular types of personal data. These laws include:

- Privacy Act of 1974 — Protects personal information maintained by federal agencies

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) — Protects personal health information (PHI)

- Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA) — Protects financial information

- Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) — Protects children’s privacy

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) — Protects students’ personal information

- California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) — Protects privacy rights for residents of California

- The New York SHIELD Act — Protects personal and private information of residents of the state of New York

What types of data are covered by U.S. privacy laws?

Information considered sensitive by U.S. laws includes:

- Personally identifiable information (PII) — Information that could be used to identify, contact or locate an individual or distinguish one person from another, such as name, address, and Social Security number

- Personal health information (PHI) — Information on health status, medical history, insurance information, and other private data that is collected by healthcare providers and could be linked to a certain person

- Personally identifiable financial information (PIFI) — Credit card numbers, bank account details, or other data concerning a person’s finances

- Student records — An individual’s grades, transcripts, class schedule, billing details, and other educational records

What is protected by the Privacy Act of 1974?

The Privacy Act of 1974 regulates the way federal government records of individuals are handled by federal agencies and requires federal agencies to follow various strict record-keeping requirements. It allows individuals to access records about themselves, learn whether those records have been disclosed, and request corrections or amendments to those records unless the records are legally exempt.

How many U.S. states have data privacy laws?

At least 16 states have data privacy laws and three of them have comprehensive consumer data privacy laws. California established the well-known California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which prompted similar legislation in Colorado and Virginia.

Do U.S. federal and state privacy laws apply to foreign companies?

It depends on several factors, including the impact on the individuals, the impact on U.S. commerce, and whether the company has a subsidiary in the U.S. Foreign businesses may be subject to U.S. laws if they collect, process, or share the personal information of U.S. residents. For example, if a foreign company does business in California and collects the personal information of California residents while the consumers are in California, it is subject to the CCPA.

How do privacy laws in the U.S. differ from the EU’s GDPR?

The GDPR is a comprehensive data privacy mandate that applies to all member states and any company in the world that collects or processes the data of EU residents. The US lacks any equivalent law; instead, data privacy is governed by a patchwork of sector-specific federal laws and various state laws.

One specific right protected by the GDPR is worth mentioning: the right to be forgotten, which is the right to request that one’s personal information is removed from an organization’s records. This right is often considered incompatible with the right of freedom of speech, enshrined in the First Amendment of the United States Constitution because forcing information to be delisted can be seen as narrowing freedom of speech and bringing the risk of censorship. Nevertheless, several laws in the U.S. do offer some form of the right to be forgotten. For instance, COPPA empowers parents to review and delete their children’s information, and the CCPA allows California residents to request deletion of their records, with certain limitations.